Thiamine (also known as thiamin or vitamin B1) is a water-soluble vitamin of the B group that was isolated for the first time in 19261. It is swiftly discharged through the urinary system, does not collect in the body, and has no harmful consequences, as are all water-soluble vitamins.

Small amounts of it must be consumed regularly as part of the diet. Thiamine is found naturally in some foods, is added to others, and is available as a nutritional supplement.

What are the functions of thiamine (vitamin B1)?

Thiamine assists several of the enzymes in the body that are involved in glucose metabolism. It aids in the conversion of food into energy. It is necessary for the growth, development, and operation of your body’s cells.2

Vitamin B1 is a strong supporter of the nervous system, and it plays an important role in the structure and integrity of brain cells.3 Thiamine (vitamin B1) contributes to the prevention of problems in the nervous system, brain, muscles, heart, stomach, and intestines.

What is the effect of thiamine (vitamin B1) on health?

Thiamin deficiency can cause a variety of difficulties in the brain and heart since it is involved in several key cell activities and the breakdown of energy foods.

Cognitive deficits

Cognitive impairments and encephalopathy are among the neurological issues that thiamine deficiency is linked to.4 Studies using animal models suggest that thiamin deficiency may contribute to the onset of Alzheimer’s disease.5

Congestive heart failure

A thiamin deficit might result in aberrant cardiac motor function. The condition known as congestive heart failure is a condition that makes it difficult for the heart to effectively pump blood to the body’s other organs. It is more common in older people, people who eat poorly, and people who take high dosages of diuretics.6

According to some clinical trials, thiamin supplementation can dramatically enhance heart function in persons with heart failure 6,7. Thiamin supplements are still being researched to see whether they can help persons with heart failure.8

Diabetes

Thiamin levels in the blood are frequently low in diabetics 9,10. Thiamine is a water-soluble vitamin that is quickly eliminated from the body and does not build up; however, because it is not patentable, neither industry nor independent donors are eager to fund extensive randomized controlled clinical trials to look into its potential for treating diabetes and its complications.10

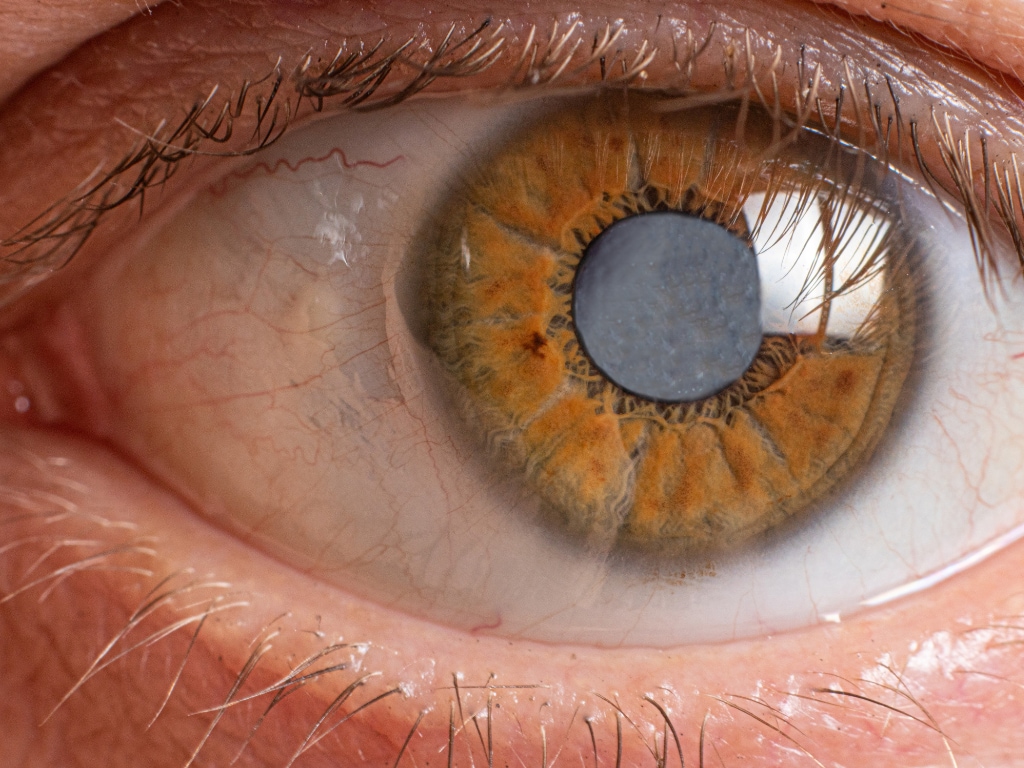

Cataracts

According to preliminary research, thiamine, together with other nutrients, may reduce the chance of acquiring cataracts. People who consume a lot of protein and vitamins A, B1, B2, and B3 (or niacin) are less prone to acquiring cataracts. Getting enough vitamins C, E, and B complex vitamins, especially B1, B2, B9 (folic acid), and B12, may help protect your eyes’ lenses against cataracts.11,12

What happens in case of thiamine (B1) deficiency?

Symptoms develop when thiamine reserves become depleted, which takes around 4 weeks after stopping intake.13

In its early stages, thiamin deficiency may lead to:13

- Weight loss

- Anorexia

- Irritability

- Confusion

- Issues with short-term memory.

Patients with chronic thiamine deficiency may experience:13

- Loss of sensation in the extremities

- Symptoms of heart failure such as swelling of the hands or feet

- Chest pain due to demand ischemia

- Feelings of vertigo,

- Double vision

- Memory loss.

- Close friends and family of the patient may also describe bewilderment or signs of confabulation.

Thiamine (B1) deficiency often affects highly aerobic tissues such as the brain, nerves, and heart first.

Wet beriberi occurs when the cardiovascular system is affected. It is characterized by:13

- High-output heart failure

- Edema and fluid retention

- Dyspnea on exertion (feeling short of breath during exercise)

Wet beriberi is a medical emergency that, if left untreated, can result in death within days. Thiamine can aid with recovery gradually, although most patients require intensive supportive care.13

Dry beriberi develops when the central nervous system is affected. This disease is typically caused by a lack of nutrition.13 It is often characterized by the following symptoms:14

- Impaired reflexes

- Symmetrical motor and sensory impairments in the extremities

- Symmetrical muscle wasting.

- Polyneuritis (a disorder affecting several or many peripheral nerves)

Wernicke-Korsakoff syndrome is a rare type of amnesia that combines two conditions:

Wernicke encephalopathy (another variation of dry beriberi) is an acute state of confusion recognized by the classic triad of confusion, ocular abnormalities, and ataxia (impairment of muscle control or coordination). Gradual mental deterioration eventually leads to the Korsakoff syndrome.13

Korsakoff syndrome (also called alcohol amnestic disorder) is a form of long-term amnesia. About 80% of individuals with untreated Wernicke encephalopathy develop Korsakoff syndrome.

Thiamine deficiency often is part of the presentation in patients with alcohol use disorder secondary to malnutrition and malabsorption, in addition to patients suffering from malnutrition.

Wernicke’s encephalopathy, Korsakoff syndrome, and Wernicke–Korsakoff syndrome are forms of dry beriberi.

Who are at risk of thiamine (vitamin B1) deficiency?

Thiamin deficiency is uncommon in the United States. Certain categories of people, however, are more likely than others to develop thiamine deficiencies:

- Chronic alcoholics 2

- Elderly 15

- HIV/AIDS patients 2

- Diabetics 9,10

- Individuals who have undergone gastric bypass surgery16

- People with digestive disorders (Crohn’s disease, celiac disease, malabsorption)

- People taking diuretics17

- People on dialysis18

- People having hypothyroidism19

- Pregnant and lactating women20

What are the food sources of thiamine (B1)?

There are numerous sources of vitamin B1. These include:21

- Whole grains

- fortified bread, cereal, pasta, and rice

- Legumes, seeds, and nuts

- Meat and fish

Brewer’s yeast has a high vitamin B1 content.22

Asparagus is an outstanding source of vitamin B1.3

Note that milled rice and grains include trace quantities of thiamine due to the processing involved in producing these dietary products.

What kind of dietary supplements containing thiamine are available?

Thiamin can be found in multivitamin/multimineral supplements, B-complex dietary supplements, and thiamin-only supplements 2,3.

Benfotiamine is a dietary supplement converted in the body to thiamine (vitamin B1). Based on its safety and clinical efficacy results, benfotiamine (BFT) is considered the preferred choice 23.

Does thiamine (vitamin B1) interact with medications?

Certain medications have been linked to thiamin deficiency in the body. Here are a couple of such examples:

Furosemide is a diuretic used to treat extra fluid in the body (edema) caused by illnesses such as heart failure, liver disease, and kidney disease. Thiamine deficiency in heart failure patients appears to be caused mostly by increased urine volume and flow rate.24

5-fluorouracil, doxifluridine, and ifosfamide are chemotherapeutic agents used to treat some cancers.25

Does thiamine (vitamin B1) interact with herbs?

Betel (areca) nuts chemically alter thiamine, making it less effective. Betel nut chewing regularly and long-term may contribute to thiamine deficiency.26

Betel nuts, also known as areca nuts

Horsetail (Equisetum arvense) contains thiaminase, an enzyme that destroys thiamine (vitamin B1). Prolonged use may result in vitamin insufficiency.27

Inform your doctor, pharmacist, and other health care professionals about any dietary supplements or prescription or over-the-counter medications you are using.

Does thiamine (B1) interact with foods?

Caffeine-containing beverages like tea and coffee contain thiaminases, enzymes that deactivate thiamine. 13 Caffeic acid, chlorogenic acid, and tannic acid in coffee, tea, and energy drinks can react with thiamine, converting it to a form that is difficult for the body to take in. This could lead to thiamine deficiency, but it is extremely rare.28

Raw fish, shellfish,13 and fermented raw fish26 contain thiaminases. Eating a lot of raw fish or shellfish can contribute to thiamine deficiency. However, cooked fish and seafood are OK. They don’t have any effect on thiamine, since cooking destroys the chemicals that harm thiamine.

Thiaminase activity is also found in several edible caterpillars (African silkworm Anaphe venata, Bombyx mori). An acute neurologic condition (seasonal ataxia) in Nigeria has been linked to thiamin insufficiency caused by thiaminase in African silkworms, a traditional high-protein meal for some Nigerians traditional, high-protein food for some Nigerians.29

What are the recommended intakes of thiamine (vitamin B1)?

The Food and Nutrition Board (FNB) of the Institute of Medicine of the National Academies (formerly National Academy of Sciences) provides dietary reference intakes (DRIs) for thiamin and other nutrients. 30

The following are the thiamine-recommended daily allowances (RDAs):

| Life Stage | RDA |

|---|---|

| Birth to 6 months | 0.2 mg |

| Infants 7–12 months | 0.3 mg |

| Children 1–3 years | 0.5 mg |

| Children 4–8 years | 0.6 mg |

| Children 9–13 years | 0.9 mg |

| Boys 14–18 years | 1.2 mg |

| Girls 14–18 years | 1.0 mg |

| Men | 1.2 mg |

| Women | 1.1 mg |

| Pregnant women | 1.4 mg |

| Breastfeeding women | 1.4 mg |

What are the recommended doses of thiamine (B1)?

To treat mild thiamin deficiency, the World Health Organization recommends daily oral doses of 10 mg thiamine for a week, followed by 3-5 mg/daily for at least 6 weeks. 31

To treat severe deficiency, the World Health Organization recommends 25-30 mg intravenously in infants and 50-100 mg in adults, followed by 10 mg daily administered intramuscularly for approximately one week, followed by 3-5 mg/day oral thiamin for at least 6 weeks. 31

Doctors determine the appropriate doses for conditions like beriberi and Wernicke-Korsakoff syndrome. Doctors give thiamine intravenously for Wernicke-Korsakoff syndrome.

What happens when we consume too much thiamine (vitamin B1)?

It is unlikely to reach a toxic level of thiamin from food sources alone. In very high intakes, the body will absorb less of the nutrient and flush out any excess amount through the urine. There is no established toxic level of thiamin.30

When should thiamine level be measured?

Thiamin levels are measured in patients with behavioral abnormalities, ocular symptoms, gait problems, delirium, and encephalopathy; or in patients with uncertain nutritional status, particularly those who appear to be at risk and are simultaneously receiving insulin for hyperglycemia.

How are thiamine levels measured?

Thiamin diphosphate (TDP) is the active form of thiamine and is the best way to determine thiamine status. Thiamine diphosphate is present in circulating blood but is undetected (present in deficient quantities) in plasma or serum.

The most robust and sensitive approach for assessing the nutritional status of thiamine and a dependable indicator of total body storage is HPLC (High-Pressure Liquid Chromatography) of TDP in whole blood.32,33

How to prepare for a thiamine test?

The patient must fast for 12-14 hours overnight. Draw before the next feeding for infants. Water can be consumed as needed. 34

How are thiamine test results interpreted?

The reference range of thiamine diphosphate is 70-180 nmol/L.35 Values for thiamine diphosphate of less than 70 nmol/L are suggestive of thiamine deficiency.

What does a too-low thiamine (vitamin B1) result mean?

Some particular reasons for vitamin B1 deficiency include:

- Inadequate dietary intake

- Diets rich in polished rice and processed grains

- Consistent alcohol consumption

- HIV/AIDS patients

- Laparoscopic gastric bypass surgery

- Digestive disorders (Crohn’s disease, celiac disease, malabsorption)

- Diarrhea

- Diuretic use

- Kidney dialysis

- Diabetes

- Pregnancy and lactation

- Hyperthyroidism

- Eating raw fish or raw shellfish, African silkworms or ferns, excessive use of tea and coffee (decaffeinated or caffeinated) (all contain thiaminase, an enzyme which degrades thiamine).

Disclaimer: This article contains information that should not be used in place of medical advice. We encourage you to discuss your interest in, questions about, or usage of dietary supplements with your healthcare providers.

References

1. Jansen, B. C. P. & Donath, W. F. The Isolation of anti-beriberi vitamin. Geneeskundig Tijdschrift voor Nederlandsche-Indie 66, (1926).

2. Said, H. in Encyclopedia of dietary supplements (ed P.M. Coates, Betz, J.M., Blackman, M.R., Cragg, G.M., Levine, M., Moss, J., White, J.D.) (CRC Press, 2015).

3. Goldstein, M. C. & Goldstein, M. A. Vitamins and minerals: fact versus fiction. (2018).

4. Gibson, G. E. et al. Vitamin B1 (thiamine) and dementia. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 1367, 21-30, (2016).

5. Gibson, G. E. et al. Abnormal thiamine-dependent processes in Alzheimer’s Disease. Lessons from diabetes. Molecular and cellular neurosciences 55, 17-25, (2013).

6. Dinicolantonio, J. J., Lavie, C. J., Niazi, A. K., O’Keefe, J. H. & Hu, T. Effects of thiamine on cardiac function in patients with systolic heart failure: systematic review and metaanalysis of randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials. The Ochsner journal 13, 495-499, (2013).

7. Schoenenberger, A. W. et al. Thiamine supplementation in symptomatic chronic heart failure: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, cross-over pilot study. Clinical research in cardiology : official journal of the German Cardiac Society 101, 159-164, (2012).

8. Wong, E. K. C. et al. Thiamine versus placebo in older heart failure patients: study protocol for a randomized controlled crossover feasibility trial (THIAMINE-HF). Pilot and feasibility studies 4, 149, (2018).

9. Beltramo, E., Berrone, E., Tarallo, S. & Porta, M. Effects of thiamine and benfotiamine on intracellular glucose metabolism and relevance in the prevention of diabetic complications. Acta Diabetol 45, 131-141, (2008).

10. Beltramo, E., Mazzeo, A. & Porta, M. Thiamine and diabetes: back to the future? Acta Diabetol 58, 1433–1439, (2021).

11. Cumming, R. G., Mitchell, P. & Smith, W. Diet and cataract: the Blue Mountains Eye Study. Ophthalmology 107, 450-456, (2000).

12. Weikel, K. A., Garber, C., Baburins, A. & Taylor, A. Nutritional modulation of cataract. Nutrition reviews 72, 30-47, (2014).

13. Wiley, K. & Gupta, M. Vitamin B1 thiamine deficiency, (2022).

14. Tan, T. X. Z., Lim, K. C., Chan Chung, C. & Aung, T. Starvation-induced diplopia and weakness: a case of beriberi and Wernicke’s encephalopathy. BMJ case reports 12, (2019).

15. O’Keeffe, S. T., Tormey, W. P., Glasgow, R. & Lavan, J. N. Thiamine deficiency in hospitalized elderly patients. Gerontology 40, 18-24, (1994).

16. Attaluri, P., Castillo, A., Edriss, H. & Nugent, K. Thiamine Deficiency: An Important Consideration in Critically Ill Patients. The American journal of the medical sciences 356, 382-390, (2018).

17. Wilcox, C. S. Do diuretics cause thiamine deficiency? The Journal of laboratory and clinical medicine 134, 192-193, (1999).

18. Ueda, K. et al. Severe thiamine deficiency resulted in Wernicke’s encephalopathy in a chronic dialysis patient. Clinical and experimental nephrology 10, 290-293, (2006).

19. Bonucchi, J., Hassan, I., Policeni, B. & Kaboli, P. Thyrotoxicosis associated Wernicke’s encephalopathy. Journal of general internal medicine 23, 106-109, (2008).

20. Kareem, O., Nisar, S., Tanvir, M., Muzaffer, U. & Bader, G. N. Thiamine deficiency in pregnancy and lactation: implications and present perspectives. Frontiers in nutrition 10, 1080611, (2023).

21. Bettendorff, L. in Present Knowledge in Nutrition (eds JW Erdman, IA Macdonald, & SH Zeisel) 261-279 (Wiley-Blackwell, 2012).

22. Vrzhesinskaia, O. A. & Kodentsova, V. M. [Vitamin B1 and B2 ratio as a method of brewer’s and food yeast identification]. Voprosy pitaniia 73, 22-25, (2004).

23. Raj, V., Ojha, S., Howarth, F. C., Belur, P. D. & Subramanya, S. B. Therapeutic potential of benfotiamine and its molecular targets. European review for medical and pharmacological sciences 22, 3261-3273, (2018).

24. Katta, N., Balla, S. & Alpert, M. A. Does Long-Term Furosemide Therapy Cause Thiamine Deficiency in Patients with Heart Failure? A Focused Review. The American journal of medicine 129, 753.e757-753.e711, (2016).

25. Basu, T. K. & Dickerson, J. W. The thiamin status of early cancer patients with particular reference to those with breast and bronchial carcinomas. Oncology 33, 250-252, (1976).

26. Vimokesant, S. L., Hilker, D. M., Nakornchai, S., Rungruangsak, K. & Dhanamitta, S. Effects of betel nut and fermented fish on the thiamin status of northeastern Thais. The American journal of clinical nutrition 28, 1458-1463, (1975).

27. Fabre, B., Geay, B. & Beaufils, P. Thiaminase activity in Equisetum arvense and its extracts. Plantes médicinales et phytothérapie 26, 190-197, (1993).

28. Marrs, C. & Lonsdale, D. Hiding in Plain Sight: Modern Thiamine Deficiency. Cells 10, (2021). http://dx.doi.org/10.3390/cells10102595

29. Nishimune, T., Watanabe, Y., Okazaki, H. & Akai, H. Thiamin is decomposed due to Anaphe spp. entomophagy in seasonal ataxia patients in Nigeria. The Journal of nutrition 130, 1625-1628, (2000).

30. Dietary Reference Intakes for Thiamin, Riboflavin, Niacin, Vitamin B6, Folate, Vitamin B12, Pantothenic Acid, Biotin, and Choline. (Institute of Medicine. Food and Nutrition Board., Washington (DC), 1998).

31. World Health Organization. Thiamine Deficiency and Its Prevention and Control in Major Emergencies.

32. Gentili, A. & Dal Bosco, C. in Handbooks in Separation Science (eds Salvatore Fanali et al.) 733-786 (Elsevier, 2023).

33. Spitzer, V. & Höller, U. in Encyclopedia of Analytical Science (eds Paul Worsfold, Alan Townshend, & Colin B T Poole) 147-159 (Elsevier, 2005).

34. https://www.mayocliniclabs.com/test-catalog/Overview/42356#Specimen>

35. Lu, J. & Frank, E. L. Rapid HPLC measurement of thiamine and its phosphate esters in whole blood. Clinical chemistry 54, 901-906, (2008).

Sign Up for Our Email List

Get our latest articles, healthy recipes, tips, and exclusive deals delivered straight to your inbox with our newsletter.

We won't send you spam. Unsubscribe at any time.